SOURCE: ENS

Army Chief General M M Naravane said on Friday (May 15) that Nepal’s protest against a newly built Indian road in Uttarakhand, up to Lipu Lekh pass on the China border, was at “someone else’s behest”. His statement has been widely taken to mean that Nepal was acting as a proxy for China, at a time when tensions have spiked sharply on the LAC between the Chinese PLA and and the Indian Army at Ladakh.

The road is far from the present scene of tension in Ladakh. It is on the route of the annual Kailash Masarovar Yatra, which goes through Uttarakhand’s Pithoragath district. Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, who inaugurated it on May 8, said the road, built by the Border Roads Organisation, was important for “strategic, religious and trade” reasons. The 80 km road goes right up to the Lipu Lekh pass on the LAC, through which Kailash Mansarovar pilgrims exit India into China to reach the mountain and lake revered as the abode of Siva. The last section of 4 km of the road up to the pass still remains to be completed.

An official statement said what used to be a difficult trek to the gateway, situtated at 17,060 ft, would now be an easy road trip. Although some officials have said it should be possible to complete the entire distance from Delhi to Lipu Lekh in 2 days, the sharp rise in altitude from 6,000 ft at Ghatiabagarh, where the new road starts, may require a slower journey for better acclimatisation, at least for pilgrims.

The government has underlined that through this improved route, yatris do not need the alternative routes now available for the pilgrimage, one through the Nathu La border in Sikkim and the other via Nepal, which entailed “20 per cent land journeys on Indian roads and 80 per cent land journeys in China … the ratio has been reversed. Now pilgrims to Mansarovar will traverse 84 per cent land journeys on Indian roads and only 16 per cent in China.”

The defence minister called it a “historic” achievement has he opened the road via video conferencing.

The new road is also expected to provide better connectivity to Indian traders for the India-China border trade at the Lipu Lekh pass between June and September every summer.

Importance of the road

Building roads leading to the contested LAC with China has been a fraught exercise for the government. The India China Border Roads as they are known, were conceptualised in the late 1990s by a consultative group called the China Studies Group, cleared at the highest level of the Cabinet Committee on Security, and given the go-ahead for construction in 1999.

But the deadlines were movable targets, and it was only in the wake of the 70-day Doklam stand-off with China in 2017, that India realised with shock that most of those roads had remained on the drawing board. In all those years, only 22 had been completed.

The Standing Committee on Defence, in its 2017-2018 report, noted that “the country, being surrounded by some difficult neighbours, with a view to keeping pace, construction of roads and development of adequate infrastructure along the borders is a vital necessity”.

The parliamentary committee demanded a higher budgetary allocations for the BRO. Another report on border roads, submitted by the Standing Committee in March 2019, flagged the ICBRs as a crucial element in “effective border management, security and development of infrastructure in inaccessible areas adjoining the China Border”.

Is Nepal’s objection new or sudden?

On the day the road was inaugurated, there was an outcry in Nepal.

The next day the Nepal Foreign Ministry issued a statement expressing disappointment over New Delhi’s “unilateral” act, which it said, went against the spirit of the bilateral “understanding… at the level of Prime Ministers” to sort out border issues through negotiations.

It asked India to “refrain from carrying out any activity inside the territory of Nepal.” The Indian envoy in Kathmandu was summoned by the Nepal Foreign Ministry.

Some in India ask why Nepal was silent through the time that the road was being built, and has objected to it now.

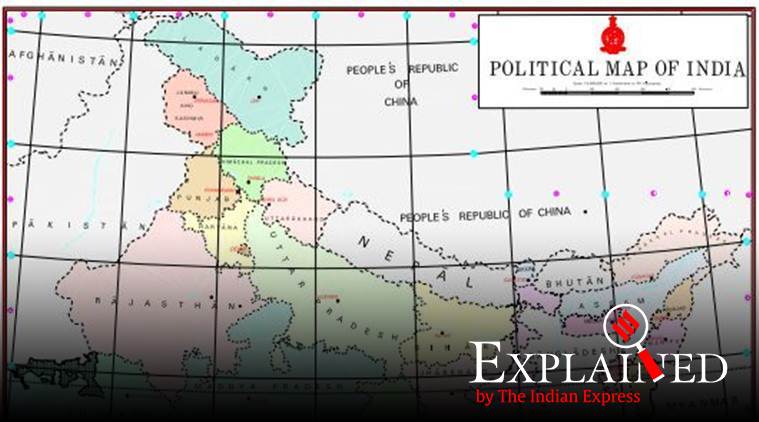

But Kathmandu has pointed out that it has brought up its concerns on the border issue several times, including in November 2019, when Delhi put out its new political map of India to show the bifurcation of Jammu & Kashmir.

Nepal’s objection then was the inclusion of Kalapani in the map, in which it is shown as part of Uttarakhand. The area falls in the trijunction between India, China and Nepal.

The publication of the map brought protesters out on the streets. The ruling Nepal Communist Party and the opposition Nepali Congress also protested. The Nepal government described India’s decision as “unilateral” and claimed that it would “defend its international border”, while the Ministry of External Affairs then said that map “accurately reflects the sovereign territory of India”.

Nepal is right in pointing out that the border issue is not new, and has come up now and again in the bilateral relationship since the 1960s.

In the 1980s, the two sides set up the Joint Technical Level Boundary Working Group to delineate the boundary, which demarcated everything except Kalapani and the other problem area in Susta.

When it was discussed at the prime ministerial level in 2000, between Atal Bihari Vajpayee and B P Koirala during the latter’s visit to Delhi, both sides agreed to demarcate the outstanding areas by 2002. That has not happened.

The Nepal-India border was delineated by the Sugauli Treaty of 1816, under which it renounced all territory to the west of the river Kali, also known as the Mahakali or the Sarada river. The river effectively became the boundary.

The terms were reiterated by a second treaty between Nepal and Briitsh India in 1923. The rival territorial claims centre on the source of the Kali.

Nepal’s case is that the river originates from a stream at Limpiyadhura, north-west of Lipu Lekh. Thus Kalapani, and Limpiyadhura, and Lipu Lekh, fall to the east of the river and are part of Nepal’s Far West province in the district of Dharchula.

New Delhi’s position is that the Kali originates in springs well below the pass, and that while the Treaty does not demarcate the area north of these springs, administrative and revenue records going back to the nineteenth century show that Kalapani was on the Indian side, and counted as part of Pithoragarh district, now in Uttarakhand. Both sides have their own British-era maps as proof of their positions.

India-China-Nepal

Since the 1962 war with China, India has deployed the ITBP at Kalapani, which is advantageously located at a height of over 20,000 ft and serves as an observation post for that area.

Nepal calls it an encroachment by the Indian security forces. Nepal has also been unhappy about the China-India trading post at Lipu Lekh, the earliest to be established between the two countries.

Shipkila in Himachal followed two years later, and Nathu La only in 2006.

Nepali youth protested in Kalapani, and there were protests in Nepal’s Parliament too when India and China agreed to increase border trade through Lipu Lekh during Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to Beijing in 2016.

At the time, Global Times, an accurate barometer of what the Chinese state is thinking on any international issue, declared that Beijing should remain “neutral” and be mindful of the ”sensitivities in the India-Nepal relationship”.

A year later, during the Doklam crisis, a senior official in the Chinese Foreign Ministry raised temperatures by suggesting that India would not be able to do anything if the PLA decided to walk in “through Kalapani or into Kashmir, through PoK”, both trijunctions like Doklam.

Though China has said nothing about the road construction to Lipu Lekh, it has protested similar road building activity at other places on the Indian side close to the LAC, including Ladakh.

In view of all this, Kalapani and the approach to Lipu Lekh has only grown in strategic importance for India, especially as relations between the two countries have remained uneven over the last few years, and China has upped its game for influence in India’a neighbourhood.

India’s tacit support to a blockade of the landlocked country during protests over the new Constitution in Nepal by the Madhesi community was an inflection point in the relationship.

Despite the open border with India and the people to people contact through the hundreds of thousands of Nepali people who live and work in this country, the levels of distrust in Nepal about India have only increased.

For its part, India perceives Nepal to be tilting towards China under the leadership of Prime Minister K P Oli and his Nepal Communist Party. Responding to Nepal’s protests, India has said it is ready to discuss the matter at foreign secretary level talks between the two countries.

The talks were meant to be held earlier this year, but were put off due to the COVID outbreak.

from Indian Defence Research Wing https://ift.tt/3cGAutI

via IFTTThttp://idrw.org

No comments:

Post a Comment